While the Nixon-Kissinger administration continued supporting military strongman General AM Yahya Khan, who launched a crackdown to “maintain the integrity of Pakistan,” a diplomat in Dhaka urged the US government to express shock, describing the atrocities in a telegram on March 27, 1971.

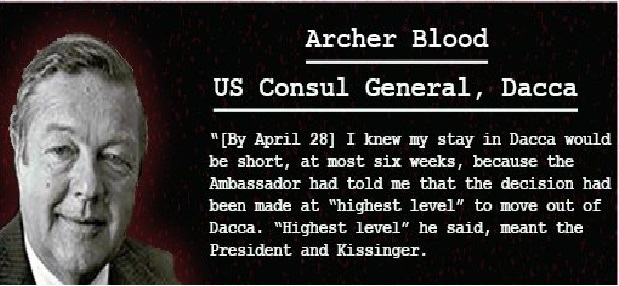

“Selective Genocide” was the title of the telegram sent by Consul General Archer K Blood. It pictured the massacre perpetrated by the Pakistani Army and the non-Bengali Muslims in Dhaka on Awami League leaders and supporters, intelligentsia, students, police and the Hindus.

Blood suggested that the US expressed shock, “at least privately” to the Pakistan government. He sent several telegrams to the State Department in the following days.

However, President Richard Nixon, advised by Henry Kissinger, remained silent even on April 2, the day the Soviet Union appealed to West Pakistan for a ceasefire.

April 6 was an eventful day. Pakistan dropped bombs in Chandpur in its first air attack on the eastern front; Jamaat-e-Islami chief Ghulam Azam, and several other senior Islamist leaders met Governor and Martial Law Administrator Lt Gen Tikka Khan lent their support to the army; and Soviet President Podgorny requested General Yahya to stop the bloodshed.

Behind the curtain occurred another incident that had a huge impact on US policymakers changing their policy towards the Pakistan conflict. Blood sent a formal dissent cable to Secretary of State William P Rogers with the signatures of 20 other diplomats, lamenting the silence of the US government over the genocide perpetrated in East Pakistan.

“Operation Searchlight” was set to be launched at 1pm on March 26, but Awami League supremo Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s proclamation of independence the previous night prompted the Pakistani military junta to start its well-designed massacre 13 hours ahead of schedule so that the Bengalis could not put up a strong resistance.

According to a White Paper published by the Pakistan government on August 5, 1971, the Awami League had plans to stage an armed revolution early on March 26.

Bravery

Blood deliberately gave a low classification to this telegram in order to encourage broad circulation in Washington, Kissinger said in his memoir.

On April 6, seven specialists on South Asian affairs from the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs (NEA), one from the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR), and another from the AID/NESA (Near East South Asia Center) sent a letter to Secretary Rogers associating themselves with the views expressed in the Blood’s telegram.

“Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy, ironically at a time when the USSR sent President Yahya a message defending democracy, condemning the arrest of the leader [Sheikh Mujibur Rahman] of democratically elected majority party (incidentally pro-West) and calling for end to repressive measures and bloodshed.

“In our most recent policy paper for Pakistan, our interests in Pakistan were defined as primarily humanitarian, rather than strategic. But we have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awami conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, is purely internal matter of a sovereign state,” Blood wrote in the Telegram.

“Private Americans have expressed disgust. We, as professional public servants, express our dissent with current policy and fervently hope that our true and lasting interests here can be defined and our policies redirected in order to salvage our nation’s position as a moral leader of the free world.

“I believe the views of these officers, who are among the finest US officials in East Pakistan, are echoed by the vast majority of the American community, both official and unofficial. I also subscribe to these views but I do not think it appropriate for me to sign their statement as long as I am principal officer at this post.

“My support of their stand takes on another dimension. As I hope to develop in further reporting, I believe the most likely eventual outcome of the struggle underway in East Pakistan is a Bengali victory and the consequent establishment of an independent Bangladesh. At the moment, we possess the goodwill of the Awami League. We would be foolish to forfeit this asset by pursuing a rigid policy of one-sided support to the likely loser.”

‘Dubious legitimacy’

Ambassador Joseph S Farland in Islamabad supported the principle that members of his mission had the right to express their views on the problems facing the US in the crisis developing in Pakistan.

He noted that the Islamabad embassy had also submitted a proposal to register serious concern about developments in East Pakistan, and suggested that it was time to review the policy toward Pakistan that excluded interference in its domestic affairs.

The strong stance of the 30 US diplomats in Dhaka and one in Islamabad worked like magic: the next day, April 7, the US government appealed to West Pakistan “publicly” for a ceasefire.

The State Department responded on April 7 in a telegram to Dhaka, saying that the US had failed to denounce the actions taken by Pakistan’s army in East Pakistan. But the State Department had not been silent about the conflict in East Pakistan.

Secretary Rogers said he reviewed a number of statements made by the department spokesman between March 26 and April 5. One of the statements expressed concern about the “loss of life, damage and hardship suffered by the people of Pakistan,” but none of them addressed the atrocities reported from Dhaka.

On April 10, the dissenting members in Dhaka sent a follow-on telegram to the State Department in which they characterized the martial law regime in East Pakistan as being of “dubious legitimacy” and took further issue with the view that the “current situation should be viewed simply as constituted government using force against citizens flouting its authority.”

They concluded that it was “inconceivable that the world could mount a magnificent effort to save victims of last Novemberʼs cyclone disaster on one hand, and on the other condone indiscriminate killing of the same people by an essentially alien army defending interests different from those of the general populace.”

Punishment

Blood lost his job; he was swiftly transferred to Washington, to a position in human resources since his steps had infuriated Nixon and Kissinger.

Kissinger also took action against other officials taking the side of Bangladesh, terming them “sick bastards.”

“They are basically pro-Indian. They want to believe what the American press is writing. And the Indian press, of course, the American press is the same as the Indian press, follows everything they say,” he said at the July 28 meeting. About Blood, Nixon said: “He’s bad, isn’t he?”

The head of the USIS was also removed because he was “tendentious in his reporting.”

Then Kissinger targeted Eric Griffel, who was the head of AID (associate director in charge of AID operations in Dhaka) and was set to be out in September.

Reactions of Nixon, Kissinger

When President Nixon discussed the reports of atrocities in East Pakistan briefly with Kissinger in a telephone conversation on March 28, he agreed with the position taken by the Embassy in Islamabad: “I wouldn’t put out a statement praising it, but we’re not going to condemn it either.”

On March 29, in a telephone conversation with Kissinger, Nixon wished Gen Yahya well when his adviser said the military ruler had control of East Pakistan.

During another phone call between the duo the following day, President Nixon asked Kissinger what the US could do but help the Indians. “…The main thing to do is to keep cool and not do anything. There’s nothing in it for us either way,” he added.

Kissinger replied: “It would infuriate the West Pakistanis.”

Turning to the role of US envoys, Kissinger said Blood did not have the strongest nerves. Nixon replied that Keating too did not have nerves. “They are all in the middle of it…,” he said.

Other telegrams by Blood

On March 28, the envoy sent the first telegram on the atrocities, terming it “selective genocide.”

Blood said they were mute and horrified witnesses to a reign of terror by the Pakistan military and recommended that the US express shock to the Pakistani authorities.

He stated that the Pakistani authorities had a list of Awami League supporters whom they were systematically eliminating by seeking them out in their homes and shooting them down. He said student leaders and Dhaka University faculty members were among those marked for extinction and named several teachers. “Also on the list are the bulk of MNAs elect and number of MPAs.”

With the support of the Pakistan military, non-Bengali Muslims were systematically attacking poor people’s quarters and murdering Bengalis and Hindus. The streets of Dhaka were aflood with Hindus and others looking to get out of the city.

He added that a curfew was imposed “to facilitate Pak military search and destroy operations” and that there was no resistance to the military.

On March 29, he reported that the army was setting houses on fire and shooting people as they emerged from the burning houses. The Pakistani army was seeking to terrorize the population of East Pakistan in general and thereby crush any resistance.

The military also wanted to “eliminate all elements of society that pose a potential threat to the consolidation and maintenance of martial law authority,” he added.

Blood said there were reliable reports of troops engaged in looting homes, beating those who objected, including middle-level government officials, and shaking down the refuges. On the other hand, the military was standing by while non-Bengalis looted Bengali dwellings, thereby abetting criminal tensions.

On March 30, Blood sent another telegram to Washington, saying the army had killed a large number of unarmed students at Dhaka University. He added that the systematic destruction of academic records at the university suggested that a campaign was underway to erase all traces of the current “troublemaking” generation at the university.

The US Embassy in Islamabad concurred in expressing its sense of horror and indignation at the “brutal, ruthless and excessive use of force by the Pak military,” but said that no matter how deplorable the events in East Pakistan had been, they should not have been raised to the level of a contentious international political issue.

In a telegram to the State Departmemt on March 27, the US Ambassador to India, Kenneth B Keating, mentioned his meeting with the Indian Foreign Secretary Pratap Kishen Kaul. He told Kaul about the US government’s position that the present conflict was an internal matter that should be settled internally.

Keating also said he believed that it would be useful for the US to be reasonably full and frank in exchanging information on East Pakistan with the Indian government.

Blood telegram information in media

After the launch of “Operation Searchlight,” several media outlets reported the atrocities in East Pakistan, which became a concern for the US government as it remained mum. At a Senior Review Group Meeting on March 31, Kissinger asked participants whether they were planning to keep Voice of America (VOA) quiet about reports coming from the Consul General in Dhaka.

State Department official U Alexis Johnson replied that it was not VOA’s fault, it was his department Spokesman Charlie Bray’s.

“Frankly, we slipped on this. The VOA just picked up what Charlie said at the briefing. Charlie talked on the basis of his daily report. No one had briefed him on the sensitivity of the Consulate communications,” Johnson said.

According to Ambassador Farland, the Pakistan Foreign Ministry had registered a complaint about a report broadcast by the VOA, All India Radio, and the BBC, which cited Consul General Blood as the source of a report that heavy fighting was taking place in Dhaka and that tanks were being used.

Farland noted that he had denied that Blood was the source of the report despite the fact that communications between Islamabad and Dhaka had been severed. He also counselled against spreading incendiary rumours.

On April 3, Secretary Rogers said, quoting Blood, that between 4,000-6,000 people were killed in the Dhaka area over the next several days. Extensive damage was done to Dhaka University, to the offices of the newspapers supporting the Awami League, and to Hindu settlements in the heart of the capital. In Chittagong, the principal port of East Pakistan, considerable damage and fatalities also occurred.

Dhaka and Chittagong had most of the approximately 750 Americans in East Pakistan, said Rogers, adding that he had made plans to facilitate the departure within the next few days of nonofficial Americans who wanted to leave, the wives and children of American officials, and some official Americans who were considered non-essential.

Signed by

Brian Bell, Robert L Bourquein, W Scott Butcher, Eric Griffel, Zachary M Hahn, Jake Harshbarger, Robert A Jackson, Lawrence Koegel, Joseph A Malpeli, Willard D McCleary, Desaix Myers, John L Nesvig, William Grant Parr, Robert Carce, Richard L Simpson, Robert C Simpson, Richard E Suttor, Wayne A Swedengurg, Richard L Wilson, and Shannon W Wilson

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.